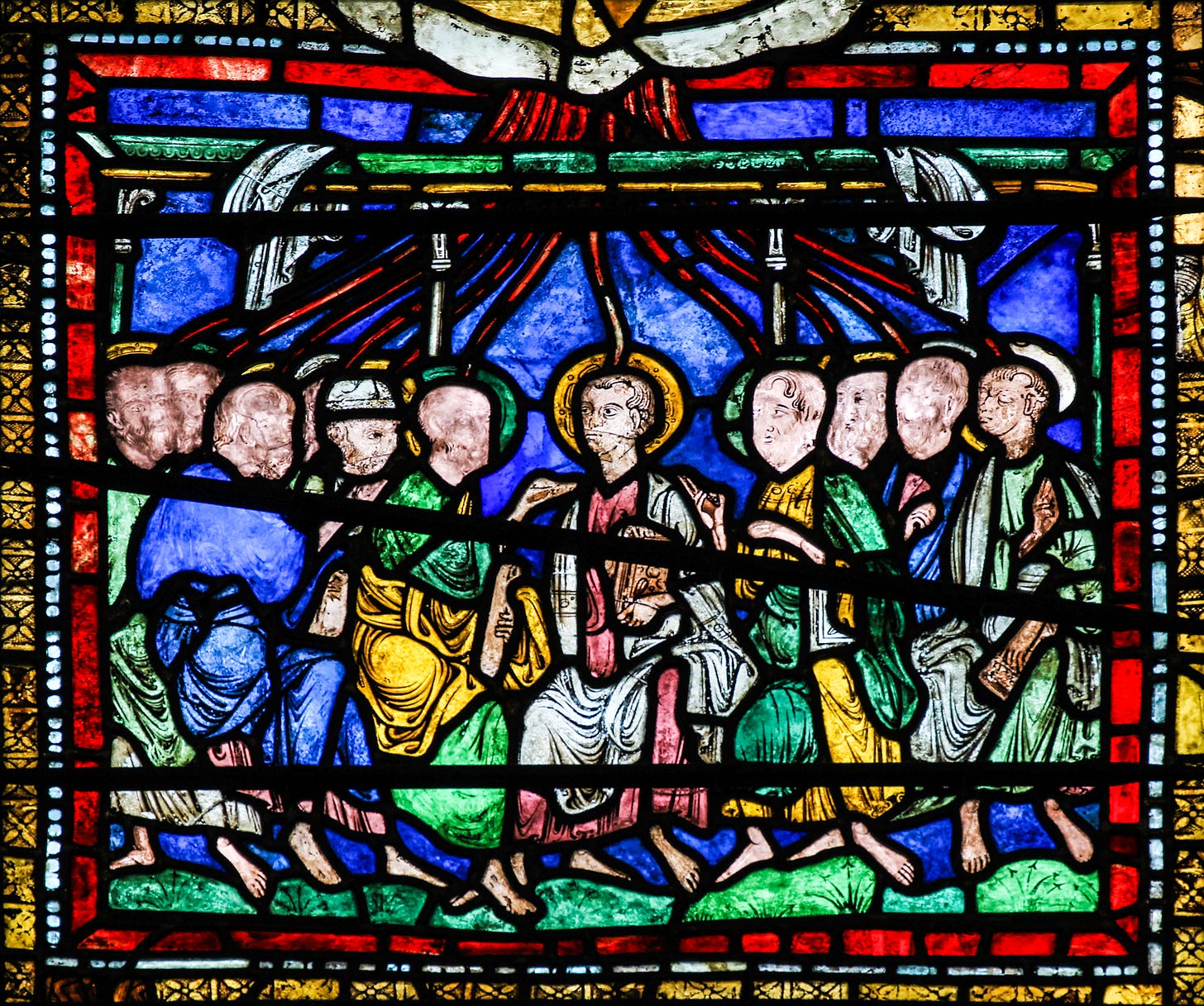

Divine Drunkenness, Mystical Madness

Why was such language once so common? Why has it nearly vanished?

Upgrade to paid to play voiceover

A toping trope

Readers who spend any extended amount of time with premodern Christian literature will not fail to come across, sooner or later, references to the “drunkenness” …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tradition and Sanity to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.